|  |

By Greg Niemann

In 1984 the newly paved road from La Paz had created an easy day trip to Todos Santos. Eventually that new road would continue to Cabo San Lucas and a more direct route to Cabo San Lucas than Highway 1.

Back then in our La Paz rental car, Leila and I, with friends Don and Marie, zoomed down to Todos Santos. I was hoping the old sugar mill town would be as charming and tranquil as I remembered from earlier visits, and I was not disappointed!

I first saw Todos Santos in June 1977 after coming up the dirt road from Cabo San Lucas, having driven Highway 1 down the length of the peninsula. That day began on a humid Cabo beach as my buddy Jon and I were startled awake by huge, stinging red ants that had the audacity to enter our sleeping bags we had just strewn on the sand in the wee hours of the night.

He and I were on Cabo’s Medano Beach, then a remote stretch of sand near a solitary hotel and little else. After a crazy night in the village of Cabo San Lucas we pulled off the highway looking for a place to sleep. We promptly got stuck in the sand and made the best of it by camping right there.

In the morning, to the delight of a few Mexicans walking past, we danced the ants off our bodies. While amused, they still exhibited the true Baja spirit and helped push our car out of the sand. After our profuse thanks, we left Cabo that morning.

The old Auto Club map showed a dirt road up the Pacific back to La Paz. After several false starts we finally found where the road left town and headed up a sandy ravine. Dodging the skinny cattle foraging in the brush we passed through a couple of ranchos before reaching the Pacific.

We cooled off in the ocean and later strolled the peaceful village of El Pescadero. I looked around the small dusty hamlet trying to see what it was that appealed to my dad. He claimed that it was his favorite Baja town.

We also immediately became enamored. A profusion of tropical flowers and plants almost concealed El Pescadero’s few rustic dwellings, most of them more picturesque than sturdy, being simply constructed from mesquite branches and thatch or adobe.

In town, animals crossed the hard-baked streets while friendly residents waved as we approached. One small, cluttered structure served as a community store. I could understand how the tranquility of the area appealed to my dad who had raised nine kids in Los Angeles.

From El Pescadero, we headed north and spent much of the day in the area's largest town, Todos Santos. The town's only roadside restaurant that we saw, the Santa Monica, was closed.

Walking down a dusty side street we found a simple thatched-roofed restaurant whose walls tried to poke through a huge clump of bright lavender bougainvillea. A Dos Equis beer sign dwarfed the small, printed lettering which modestly proclaimed the rustic building to be “Restaurant Juanita’s.”

Inside, chickens clucked beneath our feet pecking minute particles of food off the hard-packed floor as we feasted on a savory beef ranchero meal in the setting so characteristic of rural Baja.

I revisited Juanita’s the following year and established a relationship with the owner, who had learned English in Glendale, CA. We compared notes as I knew Glendale quite well.

Little change in six years

Now, six years after that last visit (1978) we four entered town. I wondered if Juanita's would still be there. It was, and the only difference this time was that instead of chickens it was a litter of puppies crawling around our feet in anticipation of us dropping some crumbs.

Sated, we strolled through town and I was delighted to see that it was still as peaceful, charming and laid back as it was previously. We toured the old Ciné Manuel Marquez de Leon, a tidy, delightful theater neatly trimmed with fresh paint and a pride of the community.

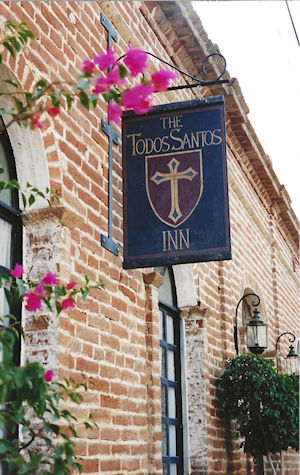

I noticed a few new businesses which blended into the timelessness of the place. One old brick building had a small hand-carved sign in front which indicated it was the “Todos Santos Inn.”

The proprietor was an energetic woodcarver who sold his crafts out of the building while his wife, an American, turned several rooms into whimsical and distinctive guest rooms. The place oozed charm and was a precursor for things to be.

The paved road up from Los Cabos that opened after our visit laid the groundwork for hordes of merchants and visitors wanting to escape the frenzy of Los Cabos.

According to a later 1997 guide “Exploring Baja by RV,” by Walt and Michael Peterson, “Todos Santos is now the home of a number of painters, potters, woodcarvers and other artists, plus a growing community of American expatriate retirees, artists, surfers and loafers. With its old brick buildings, tranquility, and leisurely ways, the town is in dramatic contrast to ‘Go Go’ Cabo San Lucas.”

That 1997 book listed several hotels and inns, a number of restaurants and stores, plus an RV park and Pemex station. Apparently the growth had not foisted too much damage to the delightful, picturesque town. I did not see Juanita’s listed.

Developed in 1724

Celebrating a tricentennial this year (1724-2024), Todos Santos was first encountered by Jesuit Padre Jaime Bravo in 1724. He developed it as a visiting station from the La Paz Mission on a hill overlooking a broad, fertile arroyo one mile from the Pacific. Farming was introduced and the area is today still known for its delicious mangoes.

In 1733, Todos Santos became a separate mission and Padre Sigismundo Taraval was its first priest. It was named Mission Santa Rosa de Todos Santos in honor of the noblewoman Doña Rosa de la Peña who donated 10,000 pesos for its support.

The mission was wiped out by rebellious Indians in 1734 but Padre Taraval and his two soldiers escaped, having been warned by faithful Indians. The mission was rebuilt and repopulated twice, first by the indigenous Guaycura brought in from La Paz who were almost decimated by a smallpox epidemic, and then by the Pericues from other missions. In 1748 the mission at La Paz was abandoned and Todos Santos received its entire population.

During the 19th Century the area was settled by mestizos. Sugar cane was introduced and several sugar mills were built to turn out small cones of panocha, a rich, dark brown sugar. The old mills still dot the valley today.

The original mission site is about a mile away at Misión Vieja and a few stones delineate the ruins. The large, whitewashed church dominating the Todos Santos town square today was originally built in 1840, but was completely rebuilt since 1941 when it was wiped out by a hurricane.

The entire mission system declined during the 19th century and by 1840 only two missions remained active, including Todos Santos.

In 1841, after the secularization of the missions, Politico Jefe Luis de Castillo Negrette declared an act to distribute the mission lands. Padre Gabriel Gonzalez, Dominican Mission president residing in Todos Santos, strenuously objected, but to no avail.According to historian Pablo L. Martinez in “A History of Lower California” Negrette had good reason for the act: “The missionaries no longer had any neophytes, but they still kept developing for their personal properties the properties of the old missions. ... This priest (Gonzalez) had carried his activities beyond the church and had been converted into a farmer, merchant, cattleman, politician, and father of a family.”

Obviously, the allure to the tranquility of Todos Santos is not a current phenomenon. Padre Gonzales had gone to the northern missions but returned to his beloved Todos Santos in 1854. It was in Todos Santos he chose to live out his life and look after the multitude of children he had reportedly produced.

The area is rich in a history of attracting those who enjoy the laid-back life and the simple pleasures amid an almost perfect climate, and still does. (The town straddles the Tropic of Cancer).

Having been back several times in more recent years, it seems to me the town has grown three-fold every time, with more expats arriving each year along with the businesses to accommodate them.

Whenever I’d walk the dusty streets of Todos Santos, I’d usually see scores of good-looking and active children wave at me or even follow me around. I envied their parents and ancestors for settling in that lovely garden spot.