|  |

By Greg Niemann

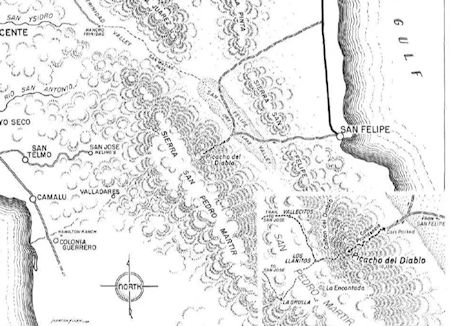

Picacho del Diablo (Devil's Peak), at 10,157 is the highest mountain on the Baja California peninsula and looms like a jagged tooth across the flat desert west of San Felipe. Alternately called Cerro de la Encantada, or La Providencia, the massive peak in the Sierra de San Pedro Mártir has long attracted mountaineers.

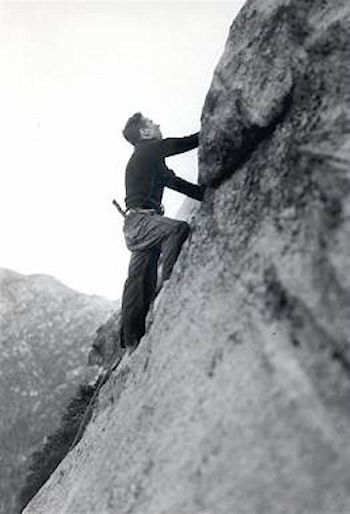

Some of the early ascents, both from the eastern and western routes, were accomplished by an elite bunch, climbers noted far beyond Baja.

The first recorded and accepted ascent was in 1911 by topographer, cartographer and prospector Don McClain, who made a solo climb of the north peak (at 10,157 is just a few feet higher than the south peak) from the western high plateau.

McClain first descended the Colorado River to San Felipe on a skiff searching for placer mines. From there he hiked to the San Pedro Mártir range and the La Grulla area at the 9,200 foot level.

To summit Picacho del Diablo from that escarpment he then descended a steep ridge and made his way up the northwest side of the Picacho del Diablo traversing huge granite blocks:

“I was able to thread my way with difficulty between these large rocks making use of some rather airy handholds and working my way over hard snow onto the east face of the summit ridge. (It was the higher north summit and McClain stated he put his business card into a thin tin tobacco box and placed a flat rock on top of it).

McClain was an outdoorsman who had worked for the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S, Forest Service, and the National Park Service. In the Angeles and San Bernardino national forests he revised the maps and supplied numerous place names still used today, including Kratka Ridge, Charlton Flat, Mt. Williamson, Mt. Lukens, and others.

An elite group of mountaineers

The second ascent, and the first to the south summit, was attained in 1932 by an elite Sierra Club group led by Norman Clyde, considered the greatest of all Sierra mountaineers. His group was made up of Bestor Robinson, Glen Dawson, Nathan Clark, Richard Jones, and Walter Brem.

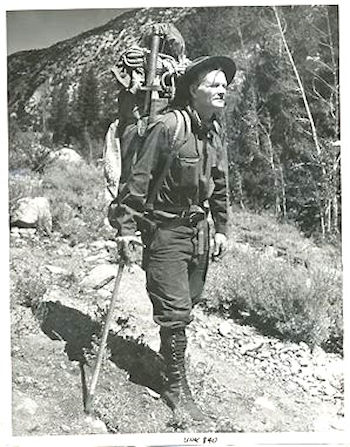

Norman Clyde (1885-1972) was a writer/photographer who became world renowned for ascending more than 1,000 peaks in his lifetime, including at least 200 first ascents! He was also known by fellow climbers for the baggage he carried (axes, shovels, cast iron cookware, even volumes of classical literature (in Greek and Latin).

He lived in the Big Pine area of the Eastern Sierra and was often called upon to locate lost climbers, the most famous instance being his discovery of the body of Walter Starr, Jr. among the crags of the Minarets in 1933.

The name of Norman Clyde endures well beyond Baja as Norman Clyde Peak, at 13,861 feet, is one of the highest of the Sierra Nevada. It is on the main ridge of the Palisades with Norman Clyde Glacier on its north face, feeding the headwaters of Big Pine Creek. Clyde Minaret, Clyde Spire, Clyde Ledge, and Clyde Meadow are some other Sierra wilderness features that now carry his name.

Those who joined Clyde on the second ascent were also well-known outdoorsmen:

Mountaineer Bestor Robinson (1898-1987) was an environmentalist, attorney, and inventor. He was a law partner of Earl Warren, later governor of California and Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court. Robinson was a long-time leader of the Sierra Club.

Glen Dawson (1912–2016) was an antiquarian bookseller, publisher, and environmentalist. The mountaineer was also part of a group, along with Clyde, to first scale the steep eastern face of Mt. Whitney. His father, Ernest Dawson (1882–1947), was also a climber, antiquarian bookseller, and served as Sierra Club president from 1934-1937. Dawson’s Book Shop also published Clyde’s account of his historic Baja climbs.

Nathan Clark (1906-1993) participated in High Sierra trips of the 1930s and early 1940s. In addition to being chairman of several club committees, he was a member of the Sierra Club Board of Directors for sixteen years, serving as president from 1959 to 1961.

Richard “Dick” Jones (1912-1995) was an active Sierra Club member for 14 years (1933-1947) and was one of the fourteen charter members of the Ski Mountaineers.

Walter “Bubs” Brem, in 1931, along with fellow teenagers Jules Eichorn and Glen Dawson completed the first ascent of Matthes Crest in Yosemite. For that challenging rock formation, the teens introduced rope climbing to Sierra Club members.

Sierra Club ascent, 1932

For that second ascent of Picacho del Diablo the Sierra Club group also climbed from the west. They left Meling Ranch and crossed over to the high point of the eastern escarpment (now known as Blue Bottle). The route to the summit looked deceptively simple to them (descend 1,500 feet into the notch and climb up the ridge to the summit). But it wasn’t!

This veteran climbing group spent all day scrambling up a ridge serrated by five deep clefts. The sun was setting and their food and water was almost gone. They had a “go or no-go” decision to make. They decided to hike off the ridge in search of water. They would retreat and try the next day if none could be found. But they found a small pool about 1,000 feet below the ridge. They bivouacked and attained the summit the next day.

They returned two days overdue, but had summited both peaks, and realized a much greater respect for Baja’s highest mountain.

Henderson tries from the east

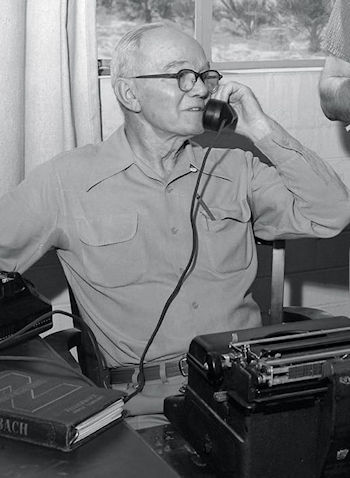

The summit had been now reached twice, both times from the west. No one had successfully conquered the peak from the eastern desert. A couple of attempts were made in 1934 and 1935, both by the same adventurer/writer, Randall Henderson, who finally succeeded in 1937.

Henderson (1888-1970) was an Army pilot in WWI and was the first pilot to ever land in Las Vegas. Known as “Mr. Desert,” in 1937 Henderson became the founder, publisher and editor of Desert Magazine, which he established in a barren cove in the Coachella Valley. He and his brother Cliff Henderson would give birth to the city of Palm Desert, California from that desert cove.

While Desert Magazine and the city of Palm Desert went on to achieve national prominence, Henderson sold the magazine in 1958 to continue his explorations. The Randall Henderson Trail is one of several tributes named for him and he was made an Honorary Life Member of the Sierra Club in 1947.

In his book On Desert Trails (Westernlore Press, Los Angeles, 1961), Henderson reveals his Baja adventures: “The high adventure of my Baja California exploration was the ascent of Picacho del Diablo.

“Malcolm Huey and I attempted to reach this summit in 1934, but we had underestimated the climbing difficulties. Our route was up Providencia Canyon, which seemed to provide the most direct route to the peak, 15 miles away.”

They were accompanied by noted El Centro attorney Harry Horton (1892-1966) and his friend W.J. McClelland, Imperial County Clerk, both familiar with Baja. Hiring a local guide named Juan, they were able to get their two “desert jalopies” with big tires across the desert to the base of Providencia Canyon. The group then spent a day scaling or detouring waterfalls, wading pools, and bucking heavy brush, reaching only the 3,500-foot level, before turning back in the morning.

A year later Henderson and Huey, this time joined by Wilson McKenney and Paul Cook, both of Calexico, made a second attempt. On the second day they camped at the 7,000-foot level, and the third day explored possible routes only to be turned back due to lack of time after they realized the summit was separated from them by a deep chasm.

Undeterred, in April 1937 Henderson made another attempt of Picacho del Diablo and was finally successful. This time he joined forces with a fellow Sierra Club member, the esteemed mountaineer Norman Clyde who had already led that successful 1932 ascent. Clyde wanted to try it from the “other side.” Henderson noted that Clyde, as usual, carried an enormous 60-pound pack and ice axe.

After he and Clyde summitted, Henderson later wrote: “....we reached the top late in the afternoon on the third day, and stood on the one point on the peninsula where it is possible to view both the Gulf of California on the east and the Pacific Ocean, where the sun was setting in the west.” They bivouacked in a sheltered cove near the summit and spent two days returning down Providencia Canyon. In a cairn at the summit they found records of the two previous ascents, and confirmed theirs was the first from the desert.

A challenging climb

While today it is summited by numerous climbers, generally from the west, it is considered a highly challenging climb and should only be attempted by experienced climbers.

One such adventurer was John W. Robinson, (1930-2018), author of Camping and Climbing in Baja, La Siesta Press, 1975. A Sierra Club leader himself, the former Costa Mesa school teacher climbed Picacho de Diablo numerous times, making his first ascent in 1958. He once also led a large group to the summit.

Robinson also wrote the introduction to Norman Clyde’s book. “El Picacho del Diablo: The Conquest of Lower California’s Highest Peak, 1932 and 1937” by Norman Clyde, Los Angeles: Dawson’s Book Shop, 1975.

Another book to consider is Jerry Schad’s “Parque Nacional San Pedro Martir-Topographic Map and Visitor's Guide to Baja’s Highest Mountains.”

According to a climber Michael Slezak, who admits online to having scaled the mountain dozens of times, “This is truly one of the finest and most challenging mountains on the North American continent (south of Canada). A very unique mountaineering experience.”

Baja’s highest peak has attracted some of the best mountaineers around, and still does. While most prevailed, they all admitted that the challenge to the top of Baja “was not as easy as it seems.”