|  |

By Greg Niemann

Today, one of the most exciting encounters Baja California visitors enjoy is to get close and actually pet a whale. Over the past few decades, whale watching excursions to the lagoons of Baja California have become a big business with numerous operators offering a wide range of trips. But it wasn’t always that way. Baja’s gentle whales were once hunted and harpooned in bloody frenzies.

Conservationists of today shudder when they recall the mass slaughter of the California gray whale in the mid-1880s. But at the time, while it was a bloody business, no one gave a thought to slaughtering the species to the brink of extinction, and whaling was considered a romantic and adventure-filled life.

While his name is synonymous with the carnage, Charles Melville Scammon was not only one of the most successful whalers of his time, he was also one of the most literate. He was a very fine artist, a self-trained naturalist and an accomplished writer. He was keenly intelligent, self- confident and destined to command.

Born in Maine in 1825, he took to sea on the East Coast and came to California with his wife in 1853. For 10 years he commanded his own whaling vessel all along the Pacific coast, hunting the gray whale from his home port of San Francisco.

He began to astonish other whalers by returning to San Francisco with a ship full of whale oil after only being out a short time. What did he know or discover that they didn’t?

Scammon had accidentally discovered a lagoon halfway down the Baja California peninsula that can be entered only through a long narrow mouth. He tried to keep his lagoon secret but other whalers from San Francisco followed him to discover where he found all the whales.

The shallow Ojo de Liebre Lagoon (Also called Scammon’s Lagoon) and the San Ignacio Lagoon are the breeding grounds of the California gray whale. Prior to the discovery by the whalers there were an estimated 18,000 to 22,000 whales migrating there each year from colder Alaskan waters.

The gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) is a formidable animal; from 16 feet at birth they can reach a length of 49 feet, weigh up to 36 tons and live between 55 and 70 years.

The common name of the whale comes from the gray patches and white mottling on its dark skin, which are scars left by parasites. They have two blowholes on top of their head, which can create a distinctive V-shaped blow at the surface in calm wind conditions.

Filling the public demand for whale oil were the adventurous whalers who now could increase their profits by increasing their yield. They headed into the Baja lagoons in record numbers. Scammon soon had competition.

Scammon wrote in 1860: "The following year found us again in the lagoon, with a little squadron of vessels, consisting of one bark and two small schooners. Although this newly discovered whaling ground was difficult of approach, and but very little known abroad—and especially the channel which led to it—yet, soon after our arrival, a large fleet of ships hovered for weeks off the entrance, or along the adjacent coast, and six of the number succeeded in finding their way in.

“The whole force pushing the whales that season numbered nine vessels which lowered thirty boats. Of this number, at least twenty-five were daily engaged in whaling. The different branches of the lagoon where the whales congregated were known as the 'Fishpond', 'Cooper's Lagoon', 'Fort Lagoon', and the 'Main Lagoon'. The chief place of resort, however, was at the headwaters of the Main Lagoon, which may be compared to an estero, two or three miles in extent, and nearly surrounded by dunes or sand-flats, which were exposed at neap tides.

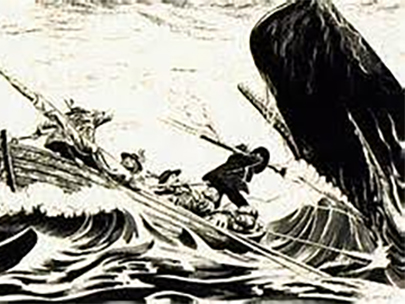

“Here the objects of our pursuit were found in large numbers, and here the scene of the slaughter was exceedingly picturesque and unusually exciting, especially on a calm morning, when the mirage would transform not only the boats and their crews into fantastic imagery, but the whales, as they set forth their towering spouts of aqueous vapor, frequently tinted with blood, would appear greatly distorted. At one time, the upper sections of the boats, with their crews, would be seen gliding over the molten-looking surface of the water, with a portion of a colossal form of the whale appearing for an instant, like a spectre, in the advance; or both boats and whales would assume ever-changing forms, while the report of the bomb-guns would sound like the sudden discharge of musketry; but one cannot fully realize, unless he be an eyewitness, the intense and boisterous excitement of the reckless pursuit, by a large fleet of boats from different ships, engaged in a morning's whaling foray.

“Numbers of them will be fast to whales at the same time, and the stricken animals, in their efforts to escape, can be seen darting in every direction through the water, or breaching headlong clear of its surface, coming down with a splash that sends columns of foam in every direction, and with a rattling report that can be heard beyond the surrounding shores. The men in the boats shout and yell, or converse in vehement strains, using a variety of lingo, from the Portuguese of the Western Islands to the Kanaka of Oceania. In fact, the whole spectacle is beyond description, for it is one continually changing aquatic battle-scene."

While Scammon’s description of the slaughter seems repugnant to most people a century and a half later, the 19th century was not known for its sensitivity in such matters. Indeed, the American bison was almost totally wiped out by “sportsmen” who shot into herds of the beasts from trains, leaving their carcasses to rot in the plains.

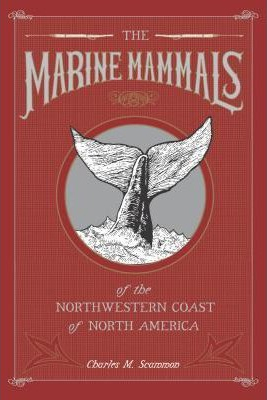

When Scammon left whaling, he returned to San Francisco and in 1874 published "Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast of North America” and “An Account of the American Whale Fishery." His wonderful pencil and water color sketches and systematic description of marine mammals were considered scientifically sound and used for decades. You can still buy his books today on Amazon.com.

Later he entered the U.S. Revenue Service and commanded a cutter in Alaskan waters until he retired in 1882. He died in 1911 at age of 86.

Once the slaughter of the California gray whales began it never stopped completely until 1937 when Mexico and U.S. forced international laws to protect the whales. The international agreement of 1938 protects all members of the species wherever found.

It appears the agreement came just in time. One source estimates that the whale population by the 1930s was down to only about 250 animals. By all accounts, the current California gray whale population is now back to its strength of 150 years ago. An Orange County Register article estimated there are 24,000 whales, even more than their historical strength.

Today’s organized whale watching dates back to 1950 when the Cabrillo National Monument in San Diego was declared a public venue for observing gray whales; the sightings attracted 10,000 visitors the first year.

Five years later, the first water-based whale watching commenced in the same area, charging customers $1 per trip to view the whales at closer range. Over the following decade, the whale watching boat trip business spread throughout the west coast.

In the late 1970s the industry mushroomed world-wide, enhanced by newer operations in New England. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s whale watching grew and operations were getting started in Baja California. By the year 2000, 11 million world-wide participants generated an income to operators and supporting infrastructure of approximately $1.5 billion.

A 2009 study estimated that 13 million people went whale watching globally in 2008. The industry generated $2.1 billion per annum in tourism revenue worldwide, employing around 13,000 workers in 88 countries.

The whale watching business is still booming, and the breeding lagoons halfway down the Pacific coast of Baja California are considered some of the world’s best venues, where personal encounters are commonplace, where the “gentle” or “friendly” whales regularly approach boats to be petted and photographed.

It’s an ecological reversal from when Scammon found a lagoon that now bears his name. He was a man of his times and did what society wanted, and did it well. His name should serve as a reminder to us of the precarious balance to nature.

About Greg

Greg Niemann is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit Greg's website.