|  |

By David Kier

The first successful California mission almost did not survive its first year or even get started on the then hostile peninsula.

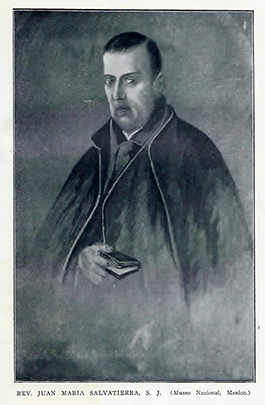

Padre Juan María Salvatierra was a human dynamo in all that he overcame to establish a new mission colony in California. Upon being granted the authority to begin the program by King Charles II, but without a peso of financial assistance from him, the Jesuit and his brothers solicited donations from wealthy Europeans to finance the conquest and created the Pious Fund.

With supplies and a pair of ships secured at the Port of Yaqui (just south of today’s Guaymas), Salvatierra awaited the arrival his fellow Jesuit and the first advocate of missions in California, Padre Eusebio Kino. Fourteen years earlier, Kino with two other Jesuits, attempted to build the first Jesuit colony in California at La Paz then again at San Bruno (15 miles north of Loreto). The colony attempt failed after two years but Kino had learned what would be needed for a mission in California to succeed: The Jesuits must have authority over the Spanish military to prevent unprovoked harm to come to the natives, and because California was so sterile it would need to be supported for a time by the successful missions on the Mexican mainland.

Sadly, Kino never returned to California. An Indian uprising at the northern Mexican missions required Kino’s attention. His superiors believed the trouble could only be dealt with by Kino. Salvatierra and crew set sail without him on October 11, 1697.

Just a mile from port the expedition’s primary ship, the Santa Elvira ran upon a sand bar. The ship was heavily laden with cargo and the fear was all would be lost. Thirty times did the ship become free only to be beached again. Help from the shore came by multitudes of canoes and the ship was finally free of the sand bar and with full sail bound for California. Sadly, the second ship El Rosario, with dried meat and flour on-board, became separated during the crossing.

Winds were a menace when they reached San Bruno preventing a landing so they headed north into the protection of Bahía Concepción, arriving there on October 15. There they found delicious pitahayas to eat but no Indians to convert. They sailed back south to San Bruno where they knew friendly natives lived that were connected to Kino’s colony of 1683-85. Indeed, some Indians were there and provided some brackish water for the visitors, who had hiked the two miles to the abandoned hilltop fort.

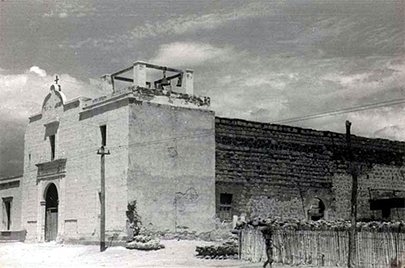

The captain knew of another location not far south that had sweet water, at a bay named San Dionisio. Salvatierra wished to begin the colony at San Bruno, but having salt-free water was critical so they sailed south at 3 p.m. on October 17 reaching the new location on Friday morning, October 18. Many Indians came to greet Salvatierra including women and children. Not far from the beach they found water and a Mesquite tree-covered mesa. The native Indian name for the site was Conchó.

On the morning of Saturday, October 19, 1697 Padre Salvatierra and Captain Juan Antonio Romero officially took possession of the land. The next four days the Jesuit and his small crew were busy unloading the clothing, corn, and flour. The Indians also helped and they were rewarded with a bit of corn. The natives enjoyed the corn so much it became necessary for the soldiers to protect it from them.

The Indians attacked the Spanish impound on November 13 from all sides. The battle lasted from noon until sundown. Several Indians were mortally wounded but not one Spaniard nor Padre Salvatierra was harmed by either the barrage of arrows or their own mortar exploding inside their compound. At sundown, the Indian chief halted the hostilities and accepted the terms imposed. Corn and flour were not free for the taking but would be distributed by the missionary in exchange for deeds performed by the Indians. Two days later, a month since it disappeared, the El Rosario arrived with its cargo of food.

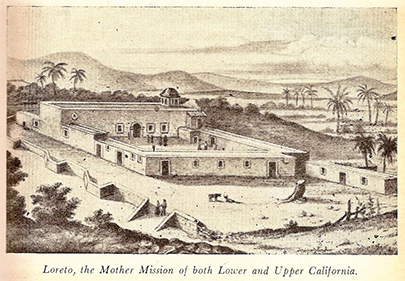

And so ends the story of the beginnings at Loreto de Conchó, the first mission of twenty-seven in Baja California and twenty-one more in Alta California. To learn more about the missions and people in Baja California during the era of conquest, missions, revolution and more, see the new book: Baja California - Land of Missions

About David

David Kier is a veteran Baja traveler and co-author of The Old Missions of Baja and Alta California 1697-1834 and author of Baja California - Land of Missions. Visit The Old Missions website to learn more and purchase these books.