|  |

By Greg Niemann

In looping the Vizcaino Peninsula back in 1990, our first destination was the fabled Malarrimo Beach, the north-facing landmass that serves as a dumping ground for the Pacific Ocean.

Ocean currents swirl southward along the coast of Baja, and the “hook” of the peninsula literally catches whatever comes her way. We’d read about adventurers finding cases of Scotch, oars, entire dinghies, full bottles, and items from all around the world—all washed up on that long, lonely beach at Malarrimo.

The biggest problem is getting there as the fickle excuse for a road is “iffy” even during the best of times. In fact the Spanish translation of Malarrimo is “Bad to get near.”

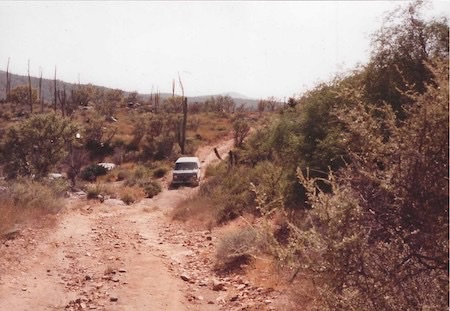

After 72 miles of rocky, graded road from the farm town of Vizcaino, we turned north onto the 27-mile dirt track that would lead us into Malarrimo. Our emergency vehicle, Ken’s motorcycle, had seized earlier and became dead weight in the van.

We wound through some narrow arroyos and crossed a rocky plateau. A horse skeleton, the bones bleached white by the unremitting sun, reminded us of our isolation. It would take about three hours to traverse the 27 miles and get to the beach, and at first it was just a typical rocky Baja road. Then the road dropped down a cliff into a narrow arroyo. For about 30 yards or so the road was so severely eroded it looked impassable in our two-wheel drive van.

In his 1973 book There It Is: Baja!, author Mike McMahan described getting into Malarrimo, “The last 17 miles were slower than a man could walk. The road follows a twisting canyon arroyo seco, a dry gulch complicated by shifting sand dunes that narrow the going. If the rocks don’t get you, the sand does.”

In that canyon, I had to physically walk areas to determine where the wheels should go. Apprehensive, we bounced down onto the canyon floor.

Large sand dunes welcomed us as we neared the beach. There was sand everywhere, even covering the road. At two spots of about 50-100 yards each, I had to rev the van up to a sufficient RPM and drove fast over the top of the sand.

Malarrimo, junkyard of the Pacific

Malarrimo turned out to be a long, wide beach, blinding white from fresh sand deposited by almost continual wind. We set up camp in the lee of a large dune and took off to scour the beach in search of booty.

There was not another person nor sign of habitation as far as we could see up or down the long beach. Nor would we see anyone the whole time at Malarrimo.

Our frisky dog Taco enjoyed the romp and sticking her discriminating nose into the sand rife with goodies from far and near. There was beach junk from everywhere. We found light bulbs with Japanese symbols on them, old hatch covers and large wooden telephone line spools, fishing floats, oars, wooden boxes, military canisters and weapons boxes, ropes, rubber sandals, caps, helmets, plastic glasses from a cruise ship's New Year’s Eve party, plastic shampoo bottles, a half intact panga and much more.

We did not find the piles of goodies that the Mike McMahan party found in 1973, nor the unopened bottles found by adventurer/author Graham MacKintosh during his walk around Baja in 1983. There was nothing of immense value but it was fun to collect. Like a grab bag, we never knew what that half-buried, colorful thing protruding from the sand might be.

That evening, I started feeling uncomfortable lest we get stuck on the way out. It would be a long walk to that one rancho 27 miles away. The van, while it had good clearance, was not 4-wheel drive, and the useless bike was extra weight.

Thus we left early the next day while we still had plenty of water and supplies. As it turned out, my concerns were for naught because we made it out of Malarrimo without difficulty.

Back on the main gravel road it was about 30 miles to Bahia Tortugas, at a population of over 3,000 the largest town on the Vizcaino Peninsula. The town was a pretty surprise. We passed scores of neat pastel-colored houses, a picturesque church on a hill and a large abalone cannery to end abruptly at the waterfront from which a long pier juts out into the sparking blue cove. Children were diving off the pier and playing in the tepid water of the bay. The almost perfectly round bay forms one of the finest natural harbors on Baja's Pacific coast. The sailing and yachting communities know the place well, and several boats bobbed just offshore in “Turtle Bay.”

The locals were friendly and especially curious to see outsiders who did not come by boat. We enjoyed a hearty but simple restaurant meal and headed 16 miles out to Punta Eugenia to camp. We passed a cluster of houses at the extreme western point and continued around to a ravine where we could look out and see Isla Natividad, a short distance away. We set up camp and fished, with Ken pulling in a beautiful 6–7-pound cabrilla.

In the morning we backtracked, passed Bahia Tortugas, and then turned south over a 37-mile dirt road over hills and down valleys to the little village of Bahia Asunción. It seemed the whole town was out on the waterfront, either swimming in the ocean, or sitting in the shade of a few nearby trees.

We set up camp on the beach just out of town and went fishing. After catching several corbina and croakers, I caught a small ray and Ken had hooked what must have been a large one before finally snapping the line.

The road south from there was a sandy track that paralleled the coast almost 50 miles to the village of La Bocana, which sits at the mouth of a small estuary.

A tire had picked up a slow leak somewhere on the rocky road. So we put to use a handy contraption for Baja, an air compressor that works off the car’s cigarette lighter. It makes a whapping noise and takes a little time putting air in the tire, but works. The townspeople delighted in watching us repair the flat.

We drove another 10 miles to Punta Abreojos on the inflated tire to a “taller llantas,” a tire shop where we had the leak repaired. Abreojos sits on a sandy spit between a point and a marsh.

It’s a small cannery town of about 500 with a few businesses and an airstrip to take their abalone and lobster to market.

The point creates outstanding waves and there were a few American surfers camped nearby taking advantage of them.

Just south of town is the Estero de Coyote, a separate estuary that abuts the northern part of the larger Laguna San Ignacio. A cluster of rustic cabins called Campo René sits on one of the fingers of land jutting into the mangrove-covered lagoon. Except for an old caretaker, Rene's was void of people. We noticed the tide rising and water touching each cabin, even completely swirling around a couple of the buildings.

The tide was rising all over, about to reach its high for the month, maybe even year, as we sought out a campsite. The road flooded in several areas so we headed into sand dunes. I chose the highest hillock I could and would later be happy for my decision.

Meanwhile, fishing beckoned. Casting into the swirling current at the mouth of the estuary’s deepest part, we were rewarded with outstanding surf fishing, most of which we released.

The incredibly bright evening skies of orange and pink began darkening as the sunset became barely visible through the clouds to the west. Exhilarated from such continuous fishing action, we hastened back to the hillock where we left the van. It was high and dry, but barely. We waded to the van which now rested on a very small island completely surrounded by water.

We could depart the next day during the low tide, but camping became a problem. Water lapped near the rear of the van and we couldn't take the motorcycle out. The cumbersome bike thus prohibited our crawling in the van to sleep, so we slept best we could in the van seats. It was a long and uncomfortable night.

From Abreojos, we completed our loop of the Vizcaino Peninsula by taking the most direct way back to Highway 1, about 50 miles of hard-packed, aggravating, rocky washboard road, finally reaching the pavement of Highway 1 about 20 miles north of San Ignacio.

This trip was over 30 years ago, but the area is still remote. Today, a paved road can whisk you to Bahia Tortugas, and another replaced the former jarring 50-mile washboard to Abreojos. Reports from recent travelers indicate the bountiful Malarrimo beachcombing days are mostly in the past, but that nasty road can still get you stuck in the sand.

*Please note that some roads featured in this article are not conventional roads, paved and dirt roads designed for the normal transit of vehicles, and our insurance coverage would not apply.

About Greg

Greg Niemann, a long-time Baja writer, is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit www.gregniemann.com.