|  |

By David Kier

History tells us about many explorers of the New World. The Jesuits explored on land and sea hoping to find places to build new missions, as well as helping the Spanish King expand his empire, and bringing more Native people into the church. In 1697, the first mission colony was founded at a place called Conchó by the Natives who lived in the area. We know that location today as Loreto.

In 1703, Fernando Consag was born in Croatia under the name Ferdinand Konscak. At the age of sixteen, he joined the Jesuits. In 1723, following years of study and training, Consag was ordained into the priesthood. In 1730, Father Fernando traveled with a group of other Jesuits across the Atlantic to North America. Once he was in Veracruz, Consag was assigned to serve in distant California. The hard journey there was so he could assist Padre Sebastián Sistiaga at Mission San Ignacio. Sistiaga was losing his assistant, Padre Sigusmundo Taraval. In 1733, Consag arrived at his new post. Padre Taraval had been assigned to the new mission of Santa Rosa de las Palmas.

By the 1740s, the Jesuits had founded fourteen California missions. Only one of which had been abandoned, the mission at Ligüí. These missions were all in the southern half of the peninsula, a place many still believed was an island. In the fifty years from the founding of Mission Loreto, they did not build any further north than the 1728 mission of San Ignacio. Consag, in addition to assisting Padre Sistiaga, traveled to other missions to assist their padres. Consag was at Mission Guadalupe in 1744 when its church wall fell and killed many people inside.

The efforts to maintain these missions and feed the neophytes were massive. Bringing supplies across the gulf from Mexico was extremely difficult with many ships lost in the crossing. A land route to California was the only hope to ensure safe communication with the mainland missions. That is if California was not an island! The peninsular nature of California had been established by earlier explorers of the Gulf of California, yet cartographers continued to show it as an island.

Even with supply difficulties, the glory of a Jesuit California was huge, and benefactors promised large sums of money to help the missionaries. They probably believed (or were told) that sponsoring a mission would guarantee an easy path to heaven. Thanks to this financial support, Jesuits began construction of proper stone churches to replace adobe and palm thatched ones. Loreto, San Javier, Mulegé, San José de Comondú, and San Luis Gonzaga all had beautiful stone-block-walled churches, built between the 1740s and 1760s.

In 1746, Spain wanted to secure California from foreign powers as well as find a land route to there from Mexico. The Jesuit Provincial, Cristóbal de Escobar y Llamas had ordered the California Jesuits to settle the question of island vs. peninsula. The Padre Visitador Juan Antonio Baltasar selected Padre Consag for this question, an excellent choice. He had been exploring the regions beyond San Ignacio where three proposed missions were planned: San Juan Bautista in the Santa Clara mountains; Santa María Magdalena in the north; and Dolores del Norte between San Ignacio and Santa María Magdalena. All three proposed missions only existed on paper but have caused speculation about the three being ‘lost missions.’ Consag began baptizing Natives on his explorations for a future Dolores del Norte mission.

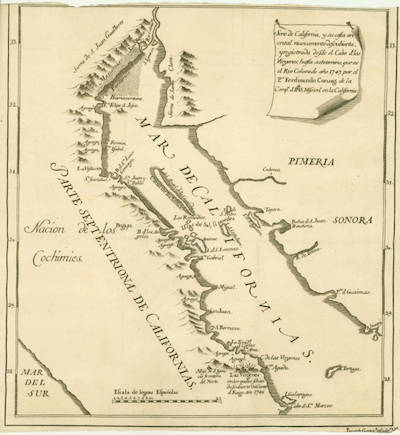

Padre Consag’s 1746 sea expedition examining the east coast of California and finding if it is connected to North America, would seem to be the final say in this question. Consag’s voyage of discovery began at the small inlet of San Carlos with four small open boats, called canoas. Accompanying him were six Spanish soldiers, a small number of his neophytes from San Ignacio, and a group of Yaqui Indians from Mexico. They set sail on June 9, 1746, and traveled by day and came ashore each night. Let me share a few entries to illustrate the level of detail which Consag enters into his diary:

On July 16th is an interesting entry where Padre Consag writes that they arrived at Bahía San Rafael and discovered hot springs by some white rocks that were covered at high tide. The hot water comes up through the sand here and other places along the same sandy beach for half a league (approx. one mile). When covered by high tide, the water is “tinged with red mixed with faint blue.” Some friendly Natives took them to the San Rafael Aguage (a fresh water source). Consag writes, “Not far from the beach is a large pond, and near it a well, which when cleansed affords good water.” This describes the lagoon near the late Pancho’s San Rafael beach camp.

July 20-22: Consag at Bahía de los Angeles had some ‘issues’ with the Natives there. Interesting reading!

July 23: The expedition reached the Bay of Remedios (today it is better known as Bahía Guadalupe). Consag describes it in great detail.

The next few days, Consag describes Isla Angel de la Guarda then the arroyos, littered with palm leaves, which caused the expedition to seek water, and they found a pond some distance up the sandy wash.

July 28, they arrive at Puerto Calamajué and named it San Pedro y San Pablo, for the anniversary of those apostles. The next day, they pass Punta Final and detail the “larger bay” and the harbor on its north end, “separated by a narrow channel” which Consag names Bahía de San Luis Gonzaga. They spent three days there but after digging a well nine feet deep, could not find water.

The diary continues with amazing details on the shoreline and the Native rancherias (settlements or family groups). Consag reaches the Colorado River and sails up it on July 18, 1746. They spent several days studying the delta so by July 25, he was confident that California was not an island.

Not having found any suitable locations for a mission on his 1746 sea expedition, a second expedition, by land this time, would look to the far north on the western slopes of the peninsula. This second expedition began on May 22, 1751, at La Piedad, a place Consag says was already picked to be the next mission [the future Santa Gertrudis] and where he had baptized many Natives for tentatively named Dolores del Norte. In 1751, Consag wrote that the spring at La Piedad had failed, and a well was some distance away. The expedition included five soldiers and a “sufficient number of natives on foot.”

An interesting passage is found on June 2: “We finally followed a small stream, the water of which looks like liquid salt. In its extremity there is a great quantity of white marble transparent like onyx. We proceeded in search of another stream, but we found ourselves very high in the Sierra already and the passage so beset with craggs that it was necessary to retreat.”

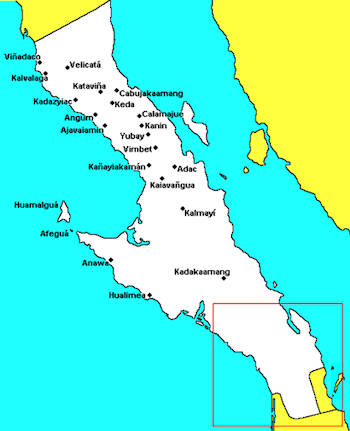

The diary again gives much detail of the land, the people and the difficulties suffered. Many times, the expedition’s meals were provided by roasting agaves and collecting the abundant shellfish. Many water sources were found but often were salty. A map locating the diary’s Native placenames would be most interesting and beneficial to see their route. Don Laylander does show five of them on his map of Cochimí placenames.

Potential mission locations were mentioned in the diary. None were ever utilized. Padre Fernando Consag, and the 1751 expedition, returned to La Piedad on July 7 and 8. Here at La Piedad, Mission Santa Gertrudis was officially founded on July 15, 1752. The year between the two events was for preparation, building, and learning the Cochimí dialect by the new California Jesuit, Padre Georg Retz. Consag’s baptized Dolores del Norte neophytes, were now members of the new mission. Consag trained Retz at San Ignacio for the year leading up to the new mission’s founding.

Fernando Consag was not satisfied with the mission-site possibilities he had seen on these two journeys. A third expedition would be needed to investigate the eastern slope of the peninsula, inland from the gulf coast. In the Spring of 1753, fifty-year-old Consag was ordered by Padre Visitador Augustín Carta to make a third expedition to find suitable mission sites. When Consag traveled, he only brought a walking stick and a section of canvas to serve his needs for the day and for the night. He was one tough padre!

The diary from the third expedition was apparently lost. We know from other works that saw in the diary; Padre Consag traveled in June and July of 1753. That he was received well at Bahía de los Angeles this time. The Cochimí men even cleared a road for him into the mountains. The expedition reached a point approximately parallel to Bahía San Luis Gonzaga. No mention is given to the oasis that would become Mission Santa María in fourteen more years, even though some modern writers claim Consag found it. The wide arroyo of Calamajué was discovered, but its water was heavily tainted with minerals and undrinkable. When Padre Linck came to Calamajué in 1766, recent rains apparently diluted the stream, fooling the Jesuits, for it was decided to build a mission there later that year, a mission that could not grow any crops. No other location visited by Consag in 1753 was promising.

They had not seen the hot spring location called Adac on the route they took. Its existence would later be disclosed to Padre Retz at Santa Gertrudis, in 1758. Padre Fernando Consag, who was then the Superior of the California missions, desired to build the new mission of San Francisco de Borja Adac. Sadly, his health and then death on September 10, 1759, would prevent that wish. Consag will be remembered as one of the Jesuit’s and Baja California’s great explorers.

References:

About David

David Kier is a veteran Baja traveler, author of 'Baja California - Land Of Missions' and co-author of 'Old Missions of the Californias'. Visit the Old Missions website.

Quick easy to navigate website

Easy, fast, and affordable.

I have been a customer for years and when I really needed them they stepped up in every way. I had...