|  |

By David Kier

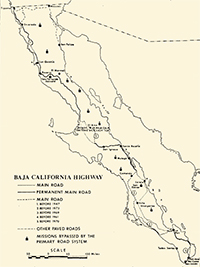

November 2023 Update: On December 1, 2023, Mexico's Federal Highway #1, known to many as 'Baja's Trans-peninsular Highway' is turning fifty years old. The long-planned and often slow progress of building a highway the length of the peninsula was put into high gear by President Luis Echeverría during his term (1970-1976). When his term began, the paving south from La Paz had just reached Cabo San Lucas and north to Villa (now Ciudad) Insurgentes. South from Ensenada, the progress was much slower, only advancing from Arroyo Seco (north of Colonet) to Camalu.

From 1970 to 1973, paving south had reached San Quintín and paving north had passed Santa Rosalia and reached San Ignacio. The big push was in 1973, to complete the highway before year's end. Many crews were put onto the project, working night and day. An entirely new roadbed was built and paved, but narrower and thinner, just to get the job done. On December 1, 1973, near Guerrero Negro, at the newly constructed, 140-foot-tall Eagle monument (photo to the left), Presidente Echeverría officially opened the new highway.

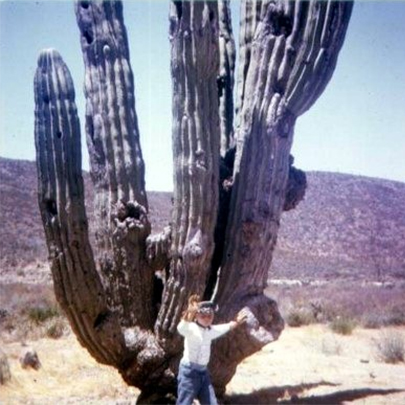

In this article below, I describe how the new highway's route compared to the old main trans-peninsular road, made so famous by authors such as Erle Stanley Gardner and Max Miller, as well as the Baja 1000 which began in 1967, and used much of the old road to get to La Paz. I was so very fortunate that my parents were adventurous and took me along as we bumped our way from Tijuana to Cabo San Lucas, in 1966 then again in 1974. What a difference eight years made to this peninsula we all love so much!

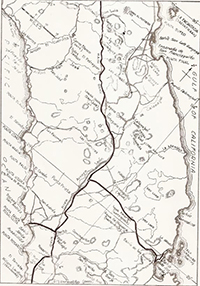

To drive an automobile from Tijuana to Cabo San Lucas was once such a rare and amazing feat that the few who did it wrote books about it. South of El Rosario, the road was just a single lane, pair of tracks, worn into the rocky and sandy soil. Signage was rare or wrong and one would simply follow the most recent looking tire tracks. The old road would split only to come back together a short distance ahead. The Automobile Club of Southern California had placed many signs at major junctions along the way, some year back in time. But the road changed with flash floods, and the signs would be shot up for target practice. Only one book gave the most details of the voyage and mileages along the way. Written by Peter Gerhard and Howard Gulick, the Lower California Guidebook was known as the ‘Baja Bible’.

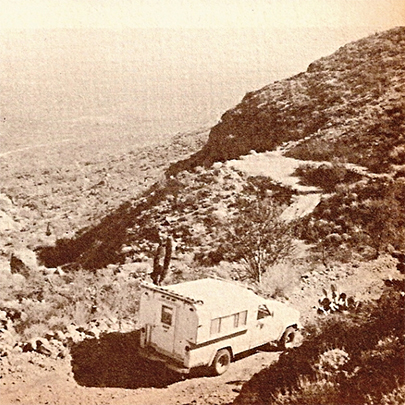

The year was 1966 and pavement ended 72 miles south of Ensenada (near Colonet). That was when I traveled the road in the family Jeep Wagoneer. My dad said, “Now the adventure begins”, and he was so right. The events that began on that day forever changed my life. I have been addicted to Baja ever since.

The next 50 miles was on a roadbed made for paving to San Quintin, but without the asphalt added. It had a ‘washboard’ surface and gave us a jarring ride. Further south, on top of a mesa overlooking El Rosario, was a stop sign. There the road dropped steeply down a ravine and without a place to pull over, the stop there allowed you to listen for any cars heading up from town before heading down.

Beyond El Rosario and all the way to San Ignacio, the main road was a deeply worn track from the a few autos and the many trucks that supplied the remote ranchos and fish camps. Four wheel drive was really the safe way to go, but many got through without it, as long as it hadn’t rained! Up to now, the new Highway used the same route as the old, but beyond El Rosario there were some changes.

The old road went a mile further east in the valley than does the highway, and the cliff ‘El Castillo’ (The Castle) was a waypoint marking where the main road headed south in a side canyon. The old road crosses south of the new highway at Km. 82/83 and heads to Rancho El Aguajito and an infamous grade that was the first traction challenge in those days. The old and new roads meet again at Km. 92/93 and stay close together for some distance. At Km. 106, the ruins of Rancho El Arenoso are just south of the highway, over on the old main road.

When the highway through central Baja was built in 1973, the villages and ranchos who catered to the few travelers looked forward to the coming prosperity. However, when engineers placed the highway out of sight from their homes, those who didn’t move to the highway lost business. Ranchos (serving as restaurants and repair shops) that moved to the highway include: El Progreso, Tres Enriques, Sonora, and Chapala.

The new highway had rest stops with gas stations, cafeterias, showers, RV parks, and most with hotels. They were called ‘Paradors’. In the undeveloped central region paradors were needed for all the new travelers the highway brought. Paradors were built at or near San Quintin, Cataviña, Punta Prieta, Guerrero Negro and San Ignacio. Over the hill, south from the rancho of San Agustín, was a gas station, RV park, and road maintenance camp of ‘San Agustin’, a mini parador. The old road is within a mile or two of the new road from San Agustín to almost Cataviña. San Agustín was the source of good drinking water for the onyx mine town of El Mármol, 10 miles away. Cataviña had been an abandoned ranch, but turned into a parador with the coming of the highway. Rancho Santa Ynez, a mile from Cataviña, was such an important stop before the highway, the ranch owner negotiated for and got a ¾ mile paved driveway to it, and a paved airport runway.

The old and new roads are next to each other the next 30 miles, crisscrossing to

the Laguna Chapala valley. The old road went across the valley, which was a bowl

of fine dust on the north and a dry lake bed on the south. The worst and best of

the old Baja road in one place! The new highway keeps to the west side of the

valley and they rejoin where then highway climbs out, on the south side. The two

roads are either in the same place or within a mile of each other to a distance

beyond Punta Prieta. The old road is exactly one mile west of the new highway at

the L.A. Bay highway junction and abandoned parador.

roads are either in the same place or within a mile of each other to a distance

beyond Punta Prieta. The old road is exactly one mile west of the new highway at

the L.A. Bay highway junction and abandoned parador.

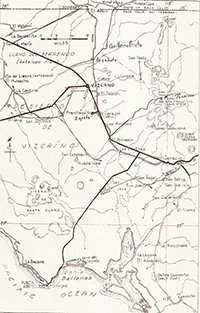

Seven miles south of Punta Prieta, the new highway climbs a ridge to the east and the old road stays lower to the west, but rejoins before the Santa Rosalillita highway junction. At Rosarito is the first major route change. The old road went south over the hills passing near the El Marmolito onyx mine and the new highway followed the valley west about three miles before turning south. The old main road headed for the center of the peninsula to the mine town of El Arco, but the new highway headed directly south for Guerrero Negro, which is also a mine town, but for salt instead of gold. Guerrero Negro was prospering while El Arco was declining. The two trans peninsular roads would meet again between Kms. 132 and 133, about 6 miles south of Vizcaíno. Of interest, the towns Cataviña and Vizcaíno, did not exist before the highway was built.

The old road stays south of the new road coming towards San Ignacio and remains next to the new road beyond the oasis town, up to the steep El Infierno Grade. The new highway turns north and drops down the side of a canyon and the old road continued east and used a series of very sharp switchbacks to drop off the side of the mountain. The two routes are nearly the same to Mulegé, but south, along Bahía Concepción, the old road followed close to the water’s edge for many miles, even splashing in the water at high tide. The new highway is further back and higher up.

Just south of Bahía Concepción is the next major split between old and new. The old main road to La Paz turned towards the center of the peninsula and passed through the twin towns of San José Comondú and San Miguel Comondú and met the graded road northbound from La Paz near La Poza Grande. Pavement going north from La Paz began about 100 miles from the city, back in 1966.

The new highway was built from Insurgentes across to the gulf at Ligüí then north to Loreto and on to Bahía Concepción. South from La Paz, pavement ended in just 10 miles in 1966, but a new roadbed was in-place to almost Los Barriles. A simple, one lane wide two track dirt road continued on to Cabo San Lucas, a small fish cannery town back then! The new road would not go through Santiago or Miraflores, but keep a couple miles to the east.

The paving of Highway One in the southern territory progressed at a rapid rate. The highway to Cabo San Lucas from La Paz was finished in 1970. The highway north from La Paz to Santa Rosalía was finished in 1972, and work was underway to San Ignacio. In the same period, south of Ensenada the highway was only paved for the 50 miles to San Quintin.

In 1973, the momentum was poured on and in the one year, the highway was built and paved from San Quintin south and from San Ignacio north, with road crews meeting at Rancho San Ignacito (8 miles south of Cataviña). No golden spike, but a small monument was placed across from the (now abandoned) restaurant. This 350 miles of highway built in 1973 was narrower than the rest and after 35 years and hundreds of accidents began to get widened in sections with a paved shoulder.

The official opening of the highway was on December 1, 1973, at the 28º parallel near Guerrero Negro where a 140 foot tall eagle monument was built. This is the southern border of the state of Baja California. The next year, Baja California Sur also became a state, thanks to the end of isolation the trans peninsular highway provided.

Quick easy to navigate website

Baja Bound Insurance has gone above and beyond for me in their customer care. I was a pain as a...

Extremely easy to acquire a policy. Many options available. Reasonable rates.